Ormai è un sollevamento generale contro abusi, misconduct, editoria predona, conflitti d’interesse e altri malanni denunciati da un decennio a questa parte.

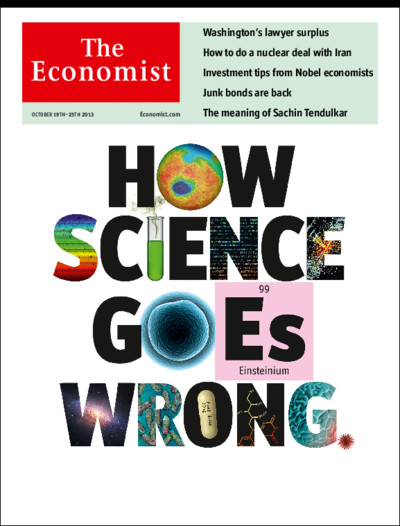

L’Economist spiega “How science goes wrong” dal suo punto di vista, ovviamente, quindi se la prende soprattutto con il pattume che danneggia di più l’economia.

L’editoriale riassume “Trouble at the Lab” che riassume le analisi di John Ioannidis e di tanti altri. Estratti per chi non ha seguito:

A SIMPLE idea underpins science: “trust, but verify”. Results should always be subject to challenge from experiment. That simple but powerful idea has generated a vast body of knowledge. … But success can breed complacency. Modern scientists are doing too much trusting and not enough verifying—to the detriment of the whole of science, and of humanity.

Too many of the findings that fill the academic ether are the result of shoddy experiments or poor analysis. A rule of thumb among biotechnology venture-capitalists is that half of published research cannot be replicated. Even that may be optimistic. … A leading computer scientist frets that three-quarters of papers in his subfield are bunk. In 2000-10 roughly 80,000 patients took part in clinical trials based on research that was later retracted because of mistakes or improprieties.

Bon, on l’savait. La sorpresa è che il settimanale che promuove la competizione ovunque dice che danneggia la scienza. Negli anni ’50,

The entire club of scientists numbered a few hundred thousand. As their ranks have swelled, to 6m-7m active researchers on the latest reckoning, scientists have lost their taste for self-policing and quality control.

Più di 10 milioni contando i dottorandi, ho letto da qualche parte.

The obligation to “publish or perish” has come to rule over academic life. Competition for jobs is cut-throat. … “Negative results” now account for only 14% of published papers, down from 30% in 1990. Yet knowing what is false is as important to science as knowing what is true.

Soliti rimedi: pubblicare tutti i dati, usare statistiche più rigorose; rafforzare la peer review o sostituirla con la post-review come in matematica – c’è un motivo perché nelle ricerche brevettabili non funziona, il libero mercato della proprietà intellettuale, ma l’editoriale su questo tace.

Lastly, policymakers should ensure that institutions using public money also respect the rules.

Ma i policy makers violano le regole per primi.

Meta-analisi dell’Economist

(grande)

L’approfondimento cita le raccomandazioni fatte al Congresso americano da Bruce Alberts, quando era ancora direttore di Science: più qualità e meno quantità, più valore attribuito ai risultati negativi, le non replicabilità elencate sotto il paper originale – facile ora che ci sono depositi come PubMed.

And scientists themselves, Dr Alberts insisted, “need to develop a value system where simply moving on from one’s mistakes without publicly acknowledging them severely damages, rather than protects, a scientific reputation.” This will not be easy. But if science is to stay on its tracks, and be worthy of the trust so widely invested in it, it may be necessary.

Di recente c’è stato un bell’esempio di errore ammesso pubblicamente e velocemente – da una scienziata, guarda caso.

*

L’Economist non cita Retraction Watch, ghe pensi mi:

– discussione del paper sull’impact factor che linkavo all’inizio del post precedente;

– Ariel Fernandez che aveva minacciato di querelare RW e ci aveva ripensato, è stato costretto a qualche correzione, e non è finita

– Dopo l’inchiesta di John Bohannon sui predoni dell’open access, un editore croato chiude una rivista

Per i predoni, vale il consiglio di sempre: controllare da Jeffrey Beall in attesa che la comunità scientifica si dia una mossa, invece di lasciarlo solo.

***

La tabella quotidiana dell’Economist è sulle vittime della schiavitù. Riporta solo una parte del Global Slavery Index di Walk Free, cmq è un pugno nello stomaco.

E il prossimo numero di Science sarà invece intitolato “How economic theory goes wrong!”. Noi abbiamo i nostri guai…ma anche loro non scherzano…

@Stefano

Speriamo, purtroppo Science vende 130 mila copie e l’Economist 1,5 milioni…

(Non te la prendere, ma cito le tue citazioni nell’ultimo post di oggi.)